Dry-Farmed Grapes and Olives: A case study of Condor’s Hope Ranch

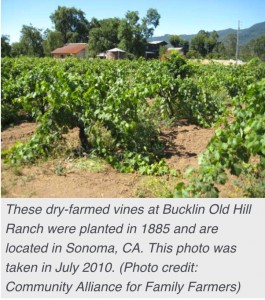

Overview of Condor’s Hope vineyard and olive trees during dry season.

Wine grapes and olives have been grown in the semi-arid and arid regions of the Mediterranean Sea for several millennia, and except for very recent historic time, were most likely grown without irrigation. Contemporary versions of this non-irrigated grape production system still exist today, in fact is some regions of southern Europe, it is illegal to irrigate out of concern for the changes that might be wrought in the quality of the wine produced. When immigrants from these regions came to California, they brought the culture of what is called dry-farming with them, with many successful examples still producing in several well-known wine growing regions of the state.

Dry-farming refers to crop production during the dry season, utilizing the residual moisture in the soil from the previous rainy season, usually in a region that receives between 20-30” or less of annual rainfall. “Dry-farming may be defined as the conservation of soil moisture during long periods of dry weather by means of tillage, together with the growth of drought-resistant plants” (MacDonald 1909). As limited water supplies, competing uses of water, and climate change put increasing pressure on water-dependent agriculture, dry-farming may once again become an attractive option.

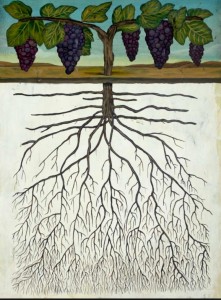

Condor’s Hope Ranch in the Cuyama Valley of northern Santa Barbara County, CA receives an average annual rainfall of 12-15”. This small family-owned and operated farm is considered to be on the margin for successful dry-farming. But since the first planting of grapes 20 years ago, and olives in the year 2000, both crops have been successfully dry-farmed and yield wine and oil of excellent quality. Despite the fact that some years have lower than average rainfall, year to year variability usually maintains enough moisture in the soil so that the plants can withstand some dry years with little or no irrigation. In order to establish new plants, an underground drip system with a riser at each plant was installed. Very light and frequent waterings are applied the first year after planting, with more time between but longer duration of waterings used in the second and third year. This trains the plants to keep going deeper for their water, and eventually establishing root systems that can tap a large below-ground soil moisture reserve. During the drought years 2012 – 2016 plant stress made it clear that the soil moisture reserves had been depleted, so additional drip irrigation was applied. But even in those years, only a total of approximately 40 gal. per plant was applied. At a planting density of 440 plants to the acre, this amounts to 17,600 gals. or just over 1/18 of an acre foot (325,851 gal per acre foot). A conventional high-density vineyard will use between 2-3 acre feet in a normal year, showing how water-saving this production system can be.

Dry farming is more than just the absence or limitation of irrigation. Plants must be spaced sufficiently to allow each plant to obtain the moisture it needs from the soil. On the alluvial sandy loam soil of the ranch, a 10’x10’ spacing is used for grapes and 20’x20’ for olives. Vines are planted on a drought tolerant and vigorous rootstock such as St. George, and the grafted varieties are heat tolerant ones such as Zinfandel and Shiraz. This means that the overall planting density is much less than conventional plantings, leading to a much lower per acre yield of fruit. The grapes are “head-trained” and free standing, rather than trained in the cordon style on wires between plants in a row. Free standing plants are necessary in this dry-farmed system, since soil cultivation for moisture management requires cross-cultivation in both directions along the plant rows.

The cultivated soil acts as a mulch keeping water in the soil.

And it is cultivation that is the key process for moisture conservation. Soil cultivation is done as soon as the rains stop at the end of the winter, and it is critical to do this while there is still moisture close to the surface and before evaporation causes much loss. The first step is to mow the vetch/oat cover crop and any vine prunings on the ground. The next step is to disc with a small conventional offset disc to incorporate the mowed organic matter. After letting the organic matter decompose for about 2 weeks, a center split disc is used to break up the soil clods and pull soil back to the center of the rows away from the plants where it was thrown by the first discing. Interestingly, the few degrees of heat generated by decomposition during this time can provide a bit of protection from light late frosts. The final and most important step in cultivation is done with a harrow with three rows of implements: the first a set of spring sweeps, the second a row of spikes, and the third a roller-chopper. This harrow leaves a uniform 3-4” thick moisture-trapping layer of dry soil termed a “dust mulch.” The word “dust” is really a misnomer, since a true dust is undesirable and highly susceptible to wind erosion. Proper cultivation leaves a dry layer of soil with good crumb structure that resists the wind. The moisture conserving capacity of the dry layer comes from the breaking of capillarity of the water column in the soil at the contact between the dry layer on top of the moist soil below. If more rain occurs and capillarity is reestablished, the harrow is pulled through the vineyard again right after the rain. No weeding needs to be done during the growing season, since all weeds were removed by the spring cultivation.

Roots of dry farmed grapes grow deep into the soil reaching water held deep in the soil.

With rainfall variability, there is also yield variability. In a wet year, about 2 tons of grapes to the acre can be harvested. But in a very dry year, yields might only be a third of that. Olive harvests seem to be much less impacted by dry years, since well established olive trees have a much deeper and extensive root system, and are hence more drought tolerant. As a means of compensating for lower and more variable yields, Condor’s Hope sells the wine and olive oil produced from its small 5 acre planting directly to consumers at Farmers’ Markets in Santa Cruz, CA and through a wine club where a more fair price is obtained for both the farmer and the buyer. Along with the product, the sustainability of the dry farm story can be told.

Reference: Macdonald, W. 1909. Dry-Farming: Its Principles and Practice. The Century Co., New York.

Excerpt From: Gliessman, S.R., 2015. Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems. 3rd Edition. CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL.